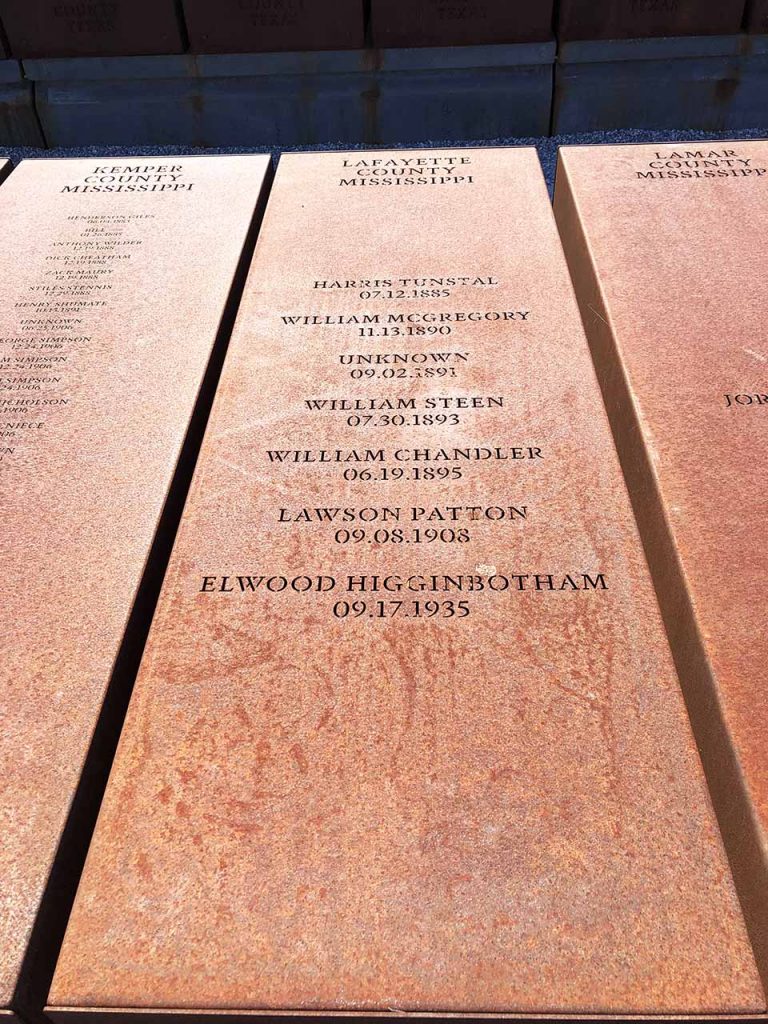

A mob hanged Harris Tunstal behind the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1885. Will McGregory was shot on the courthouse lawn in 1890. William Chandler was hanged from a telegraph pole in 1895.

The three African American men were among seven local lynching victims who may soon be memorialized on the courthouse lawn.

The Lafayette County Board of Supervisors voted 4-1 on Monday to approve language for a marker that would be placed on county land in the center of the Square. If accepted by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, it will be unveiled on Nov. 17.

The marker would be located near the monument honoring Confederate soldiers, which was erected in 1907 by the United Confederate Veterans.

Lydia Koltai, a member of the Steering Committee for Lynching Memorialization in Lafayette County, a community organization, said memorialization markers are important because they help the community see parts of its history that sometimes go unnoticed.

“Oxford has been really good at telling one story about itself for a long time now, and we’re coming into a time of, I think, telling the more full story of our history,” Koltai said. “And I think that’s important for the community to see as a way to move forward and heal from things that haven’t ever been dealt with.”

Last year, a marker was erected on the corner of North Lamar Boulevard and Molly Barr Road in memory of Elwood Higginbotham, Oxford’s last known lynching victim.

Both markers were funded by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing legal defense to individuals on death row since 1994. EJI regularly donates lynching memorials in partnership with community members in areas all over the South.

According to the EJI website, EJI has documented 4084 racial terror lynchings in 12 southern states from 1877 to 1950.

April Grayson, director of community building at the William Winter Institute and Steering Committee member, said the committee chose the courthouse lawn as the site for its next marker because of the history of the location.

“The courthouse lawn specifically in Lafayette County is significant because one of the seven lynchings actually took place on the courthouse lawn, and at least one more was in sight of that space, but historically many lynchings took place on courthouse lawns across the South and other parts of the country,” Grayson said.

Lawson Patton was shot and hanged on the grounds of the Lafayette County Courthouse in 1908 after being accused of the murder of a white woman.

Grayson also said that the Steering Committee is hoping to install markers for every known lynching victim in Oxford, but they’re still going to do as much research as they can into each victim and trying to find possible descendents in the area.

Darren Grem, associate professor of history and Southern studies and former member of the Steering Committee, said the Higginbotham marker did more for the community than memorialization. It provided Higginbotham’s family with answers.

“They had heard stories about Elwood Higginbotham (and) why the lynching occurred,” Grem said. “Some of them were true, some of them were half-truths, but the research that we were able to provide more context for them and a certain amount of coming to terms with that lynching or even a semblance of closure about it if closure is even possible.”

Board of Supervisors Vice President Chad McLarty was the only dissenting vote of the morning. McClarty took issue with the description of the lynching of Will Steen who was killed in 1893 after an alleged affair with a white woman. McLarty thought the description was “too vague.”

“I told them that if they could tweak it or change the language, then I would support the memorial marker, and they just didn’t want to change it,” McLarty said.

Grayson said that the Steering Committee’s work on memorialization could sometimes cause anxieties in the community, but it’s meant to be a way to bring people together.

“Memorialization work is a really important stepping stone in a process of healing and racial reconciliation … it’s not about reopening old wounds, but it’s really about helping a community acknowledge a more complete story, and therefore actually grow in wholeness as a community,” Grayson said.