The best way to tell my election story is backwards.

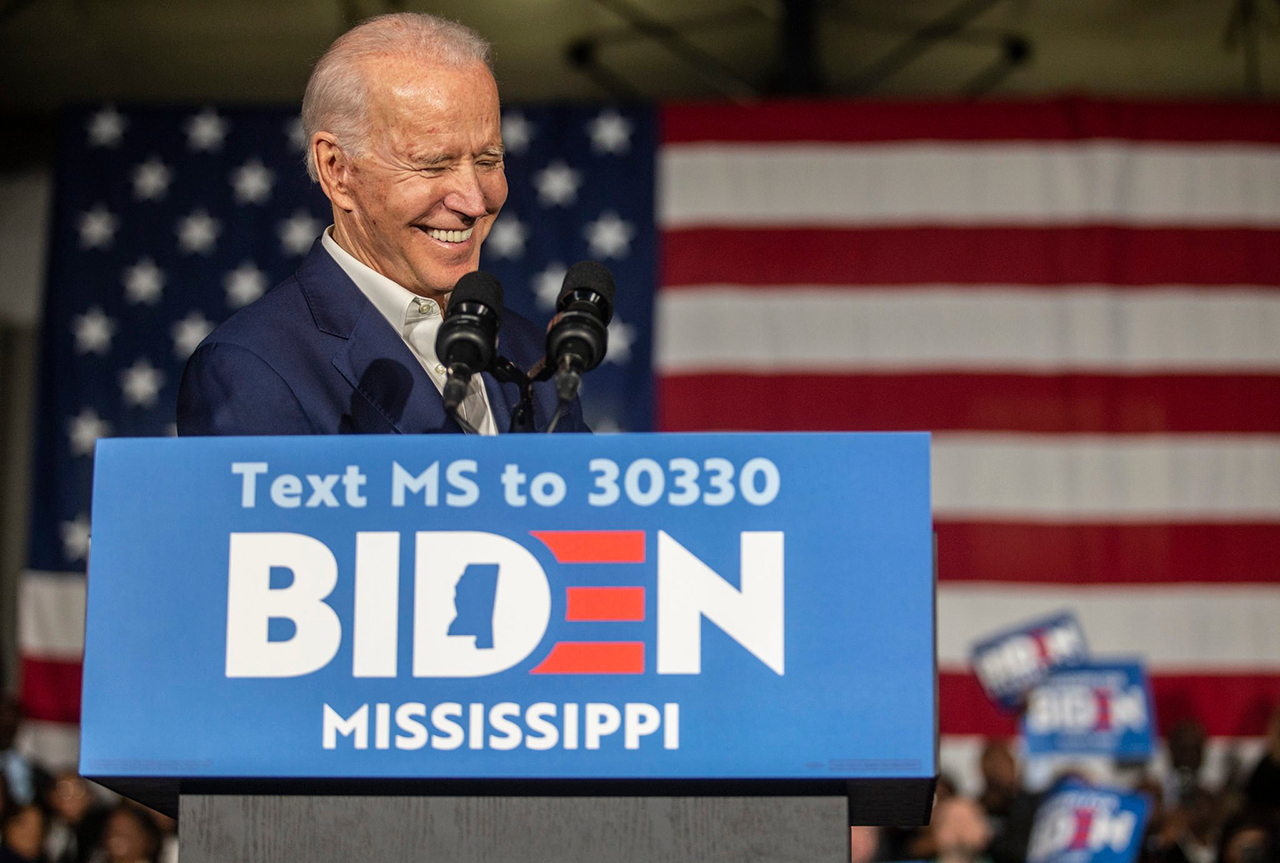

A sunlit window opens in my world, and they call Pennsylvania. I stand in line on Tuesday morning and cast my vote for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. I tune into the campaign coverage just to see Biden reading letters from children with speech impediments, to hear him admit what I already know: he still struggles, too. He once said, “Stuttering gave me the best possible window into other people’s pain.” I tune back out.

My fears are affirmed. When students in my GroupMes make fun of Biden’s supposed mental decline, I sharply remind them that pretending to forget your next phrase is a hallmark of a “well-managed” fluency disorder — and I should know. My family and friends don’t realize that the algorithm puts their posts on my timeline every time they clap back at strangers talking about Biden’s stutter. I prepare to block it out.

Biden wins the nomination. My professor tells me, “No one will ever want to work with you or give you opportunities while you still have a speech impediment.” Biden lies through his teeth about how he beat his stutter so many years ago. It’s inspiration for someone else.

When it looks like he might not win the nomination, I am relieved. When it seems like he isn’t going to run, I am relieved, though I’ll keep that from my children. I didn’t want to be dragged through it.

The pharmacist on the phone hangs up on me when I can’t get my name out. I remember that it probably hurts worse for Biden, putting himself out there like that. I think about how Biden will never see what they say. I will, and it will come from people who say they love me. I think about how much a person, even a national leader, can still be crushed by bullies. I’m in the drive-thru at Cookout giving my order, and the guys in the truck behind me hang out the window and imitate my blocked speech.

The UM Speech and Hearing Center tells me it’s not going to get better when I notice it’s getting worse freshman year and get a new diagnostic test. I graduate high school with a speech and debate cord around my neck. I compete for three years in speech tournaments and never win first place, but at least I competed. At the end of my freshman year, I go to the speech and debate interest meeting. I say, “I have something to prove to myself” when I talk my parents into it. I read a letter that Biden wrote decades ago to a young boy with a speech impediment, advising him never to let his stutter get in the way of his goals, and this idea takes shape in me — this wild what-if.